TLDR

I wanted to try experimenting with traditional java design patterns in Rust. I knew the features of Rust would mean I couldn't copy and paste them from GoF's templates.

Entries

6/13/2020 - Why Design Patterns?

6/14/2020 - Preliminary Research

6/15/2020 - Updating Old Project

6/17/2020 - Implementing User Struct

6/20/2020 - Designing Internal Api

6/22/2020 - Implementing Internal Api

6/23/2020 - Channels with Serenity

6/26/2020 - Final Thoughts and Objective Analysis

Overview

When discord announced their rust api; I worked with a friend to create a small discord bot. The bot read a music file off the filesystem and played it when the user entered the channel. It also played a file when a goal was scored in the video game, Rocket League. It wasn't particularly easy to use or robust; we made it more to learn Rust than to use it. And while we learned the basics of Rust, we never really got around to exploring how to implement more extendable designs using Rust's trait system.

Traits can be described as a more rigid way of implementing "duck typing" which is how Python handles object behavior. Instead of characterizing objects by their datatype; you define their behavior with traits and use these traits to define when they can be used. This is also similar to implementing interfaces in Java. It is supposed to be semantically clearer than using objects, since in most usage cases you really care about what an object can do; not what it is.

I typically program in Object-Oriented languages and make extensive use of design patterns when designing larger programs. I find they help make programs easier to adapt and extend, but they require forethought and careful use. Originally, design patterns were designed for Java and their explicit implementation works best there. I currently work in Computer Vision research and use Python and C/C++ at work. Both of these languages have object systems, but their nuanaces mean I always need to adapt the design pattern to both the language and use case.

Rust's traits are even more different that Java's objects. I'm curious to see how or even if design patterns still work. I do think the high level ideas(creating guidelines on solving frequent, specific types of problems) will still work in Rust. But the actual implementations may be drastically different.

I plan on using this chat bot to investigate this. I don't want it to be tied a game so I will drop the feature that plays output for scoring in Rocket League. To be more robust; I will have the bot try and use youtube videos to play music instead of a taking an audio file from the filesystem. Since I'm changing the original purpose I will fork and rename the bot. This is the new repo.

I mentioned in my previous post that I wanted to find concrete use cases for Rust. I want to clarify that this is not one. I will likely not use this bot and don't expect anybody else to. This project is more of an excercise to test out design patterns in Rust. And as I also saw in my previous entry, my ideas in this area don't always pan out. So we'll see how this one goes.

Objectives

- Refactor the old bot into one that only plays music when a user enters a channel

- Investigate design patterns in Rust with the trait system

6/13/2020 - Why Design Patterns?

What exactly are design patterns? The simplest way to describe them is that they are high level guidelines for common problems in software engineering. If a problem is concrete, you can abstract it into a library and be done. But some problems are more vague and can't easily be built into a library that's useful for most users. But these problems occur very frequently, so it makes sense to have some way to discuss them instead of vague descriptions. This is a very simple paraphrasing and for those not familiar with design patterns I'd suggest this book. It looks childish, but it's an excellent high level overview of design patterns; including good examples for using them. Most people suggest the classic Gang of Four(GoF) book, but I find this book to be too verbose for a first read. The Head First book will give you a good high level overview of design patterns, and then you can read the GoF book for more details.

One mistake people make when discussing or using design patterns is that they think of them too rigidly. Design Patterns were originally made for Java; and some say they help compensate for Java's weaknesses. Other languages don't need design patterns because they have features like higher order functions built in. But I think this is too myopic. Using design patterns exactly the way they are for Java in other languages is incorrect, yes. But if that was all that design patterns were, they could be made into a library. They're more high level guidelines and can be implemented in other languages differently.

This sounds very abstract so I'll use a concrete example with the strategy pattern. If you aren't familiar with this pattern this discussion won't make any sense, so I'd review it first. In Java, the strategy pattern is implemented by using different objects for different algorithms with a common Java interface. In Python, we could do something similar, except using duck typing and ensuring our objects have the necessary methods. But Python has higher order functions, so instead of creating objects for each algorithm, we can just pass around higher order functions instead. Java doesn't support this, so it looks like we're using design patterns to address this weakness. But I'd argue we are still using the strategy pattern in Python. The strategy pattern is creating an abstraction for some set of algorithms. In Java we do this with objects. In Python we do this with higher order functions, but our higher order functions still need a consistent interface(interface here means function prototype). So we're still creating an interface and abstracting away details of behavior, because we recognize we may want this behavior to change. This is what design patterns really are. But it's very difficult to see without an example. And it's very easy to see how some people might think the details for implementing design patterns are very rigid. Of course, even in Python, there may be situations where we should favor the object approach instead of higher order functions. It all depends on exactly what your problem is.

These kinds of problems reoccur frequently in software engineering. But their abstractness makes them difficult to describe. So design patterns also provide us with a concise vocabulary to discuss these kinds of problems. Rather than spend twenty minutes describing this problem I could say "it's the strategy pattern" or "it's a variation on the strategy pattern". Anybody who knows design patterns would instantly have a strong grasp on my problem, and be able to help me with it.

Another way design patterns help software engineers is by developing their "precognition". Once you become familiar with them; you can start recognizing them. This lets you predict how the software might evolve, and you can ask your product manager what they think. It's important not to overengineer pre-emptively, but raising these concerns in advance can help everybody think about how the software may change and what's the best way to handle that. It's a balancing act between overengineering and not digging yourself into holes, and design patterns can help identify and address these areas ahead of time.

So then are design patterns "perfect"? Of course, not, they have trade offs like every design decision and you shouldn't always use them. Always using shiny design patterns results in overengineering and can make you codebase large and unwieldly. Design patterns generally have a simple trade off. You add complexity to your software in exchange for isolating some part and allowing it to change independentally. If you know this will happen frequently it's an excellent trade off. If not, then you're adding needless complexity. Granted, most problems are rarely this black and white and you'll need to make decisions based on your case. So it's important to recognize the trade offs, both in general, and in your specific problem.

This kind of recognition ability comes with practice. Another personal example I can give to demonstrate the benefits of this is how I approach my own research code. I currently work as a computer vision researcher; when trying out different approaches I'll often start with simple python scripts with Spyder and/or Jupyter. Obviously, it makes no sense doing any serious software design here. But as I add to these scripts they can become quite difficult to use. I end up commenting out lines, or changing parameters by changing source code. I can try to use functions, but even this becomes too weak very quickly. But because of my experience recognizing and applying design patterns; when these issues show up, I can very quickly refactor my code to use them. This keeps my scripts simple and easy to use and allows me to run my experiments more confidently. Instead of scrambling through my code to make sure everything is commented out correctly. This does take some additional time, but always pays off.

A concrete example of this is when building neural networks. Hyperparameter tuning is a big part of neural network training and involves sweeping through different combinations of parameters for different network types. This ends up being a perfect fit for the builder pattern; I can use it to easily construct different networks set with whichever defaults I want for certain experiments. And it's easy to redo these experiments without having to deal without commenting out different parts of code. My familiarity with design patterns lets me do this with minimal time or thought penalties; and identify and address them very early. I make overengineering mistakes sometimes, but I always learn from them. And the time and brain bandwitdh saved more than makes up for it.

C/C++ are similar enough to Python that this carries over easily. The stronger typing and slower evolution of the code actually makes it easier to apply these techniques there. I now want to develop this skill in Rust. Rust's trait system is different than a traditional object system. I don't want to misuse this so I need to learn how to apply design patterns to Rust.

6/14/2020 - Preliminary Research

First, I wanted to see what kind of information there was on this area beforehand. I found some github repos with design pattern examples, but I didn't find this to be helpful. As I mentioned, a discussion for a specific use case is usually important to understanding design patterns. Concrete code examples without context don't really help. But the Rust docs have this. There's an entire chapter on traditional OO principles, how to use them in Rust, and which standard Rust features can be better. This is exactly what I wanted.

Reading the documentation was very helpful. They describe how to implement a basic blog using the concrete GoF state pattern; then give an example of how to do it better in Rust. The basic idea is, instead of storing a state variable, you actually tranform your object into different objects to indicate state. Rust's ownership mechanics make this possible. This kind of object transformation feels somewhat like a fusion of functional and object-oriented programming. But using types to denote state means the Rust compiler can step in and recognize when something is being used in a way that it shouldn't. But behavior is still tied to each state object so changing and adding states is the same as the state pattern.

This was a very useful example and I'm interested to see how my own project might use similar ideas. My only criticism is that the documentation seems to support the idea that design patterns are these rigid constructs and their rust implementation "isn't a design pattern". I'd argue their implementation is still using the basic ideas of the state pattern; just applied with Rust's own unique features. Nevertheless; this is a semantic criticism at best, and not worth dwelling on.

6/15/2020 - Updating Old Project

The first step should be updating the old project to get ride of the code I don't need. I'd also like to test it and make sure it works as I expect(plays music from filesystem when I join the channel).

Unfortunately, the first thing I note is the discord api I was using is no longer regularly maintained. There seems to be a new one , but this is one issue of using Rust. It lacks the popularity of other languages so edge cases like this are not likely to be maintained over long periods of time. And as I mentioned earlier, this is probably not a good use case for Rust anyways, so I can't really expect anything.

This puts me in an awkward situation. I could go ahead and implement the bot with a new api. This is only a research experiment and if it goes stale, it's not a big deal.

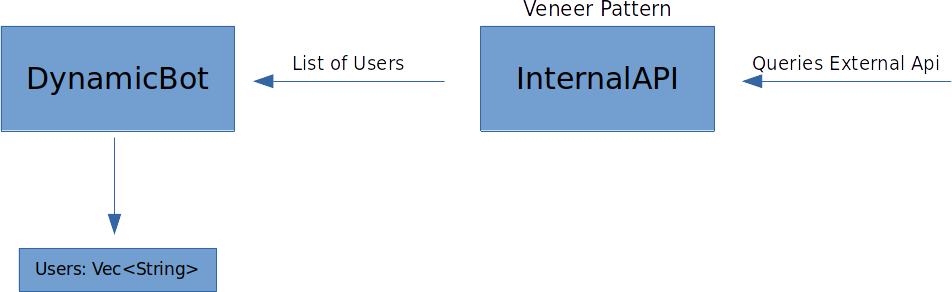

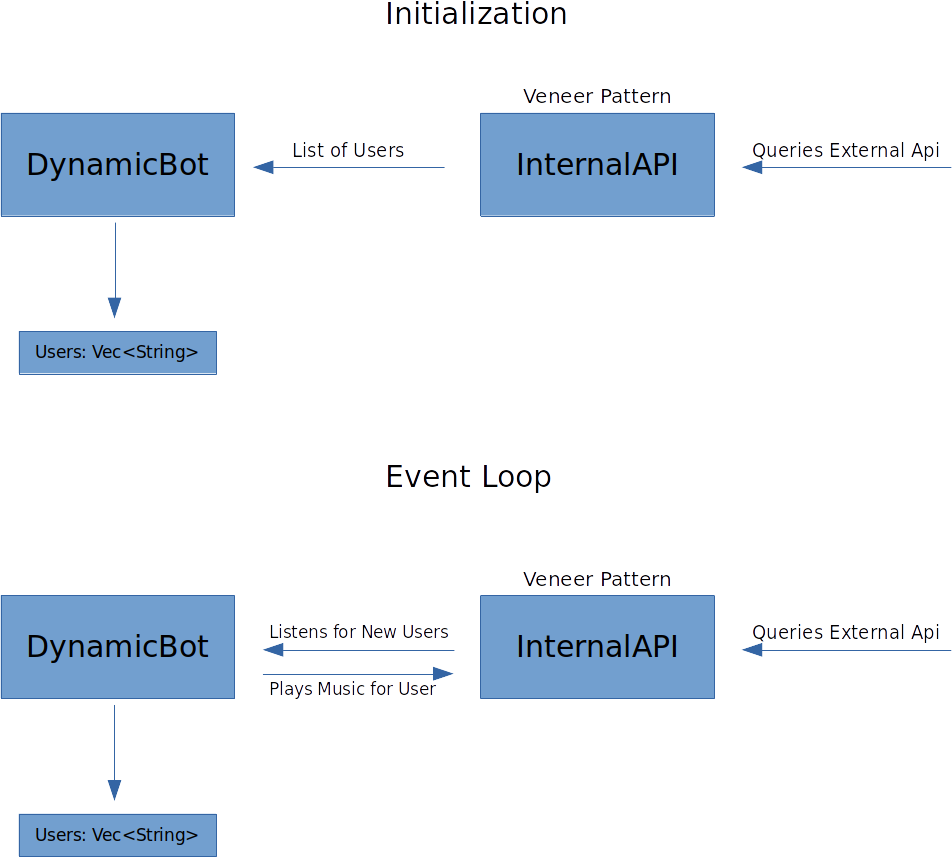

But maybe I can turn this into something. Design patterns are meant to adapt to change when it's expected. Perhaps I can design this application and abstract away the discord api. So when it does change, all I would need to do(if I wanted to update it), is make the necessary changes to this layer. This is referred to as the veneer design pattern. I'm creating an api of my own, that my code will conform to. So if the api changes, I won't need to change my own code. I just need to update my internal api

But this means; there's no point in updating this existing code. I might be able to reuse some of it, but now I need to design this application. That will be my first step.

6/16/2020 - New Design

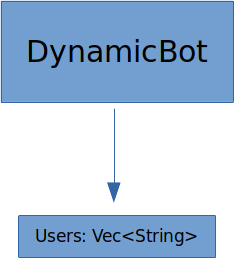

I want this bot to play music when a user enters the voice channel. So the first thing this bot needs is to keep track of everybody in the channel. I can store this as a vector of users. We'll keep them as strings for now.

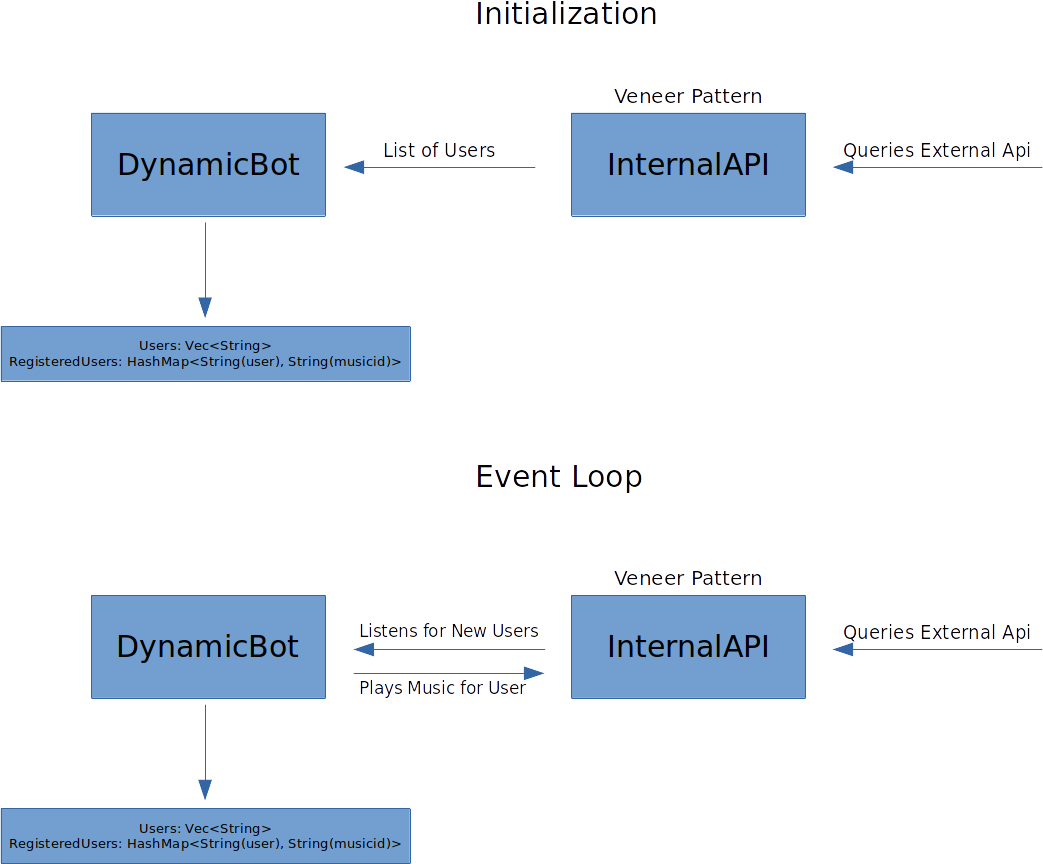

So my internal discord api will need to log in and query a list of users in the channel; which will be used to initialize my vector.

However, this will just be the initialization step. Afterwards I'll need a loop where the internal api listens to the external one and pushes updates to the DynamicBot.

So what else? Well each user will have their own music they want for their entry theme. So rather than keep this seperate, I should use a struct for each user instead of a string and store a vector of those.

Now that my sketch is complete. I want to review it. This is a pretty simple design. Most of the work will be getting the event loop to synchronize between my internal and the external api.

The veneer pattern is justified here. I expect the rust api I'm using to change so it makes sense to abstract that away.

Another pattern I considered was using a command pattern to push the music playing behavior in the the UserStructs. If I wanted to support multiple types of behavior, this would be a good idea. But I don't plan on adding any other types of behavior, so this would be needless complexity. My first task will be to implement the user structs.

6/17/2020 - Implementing User Struct

Implementing this piece should be simple. The tricky part is initialization. Each user will have a name and a piece of music for them. I don't want to store this in code, so I'll need a way to initialize these objects.

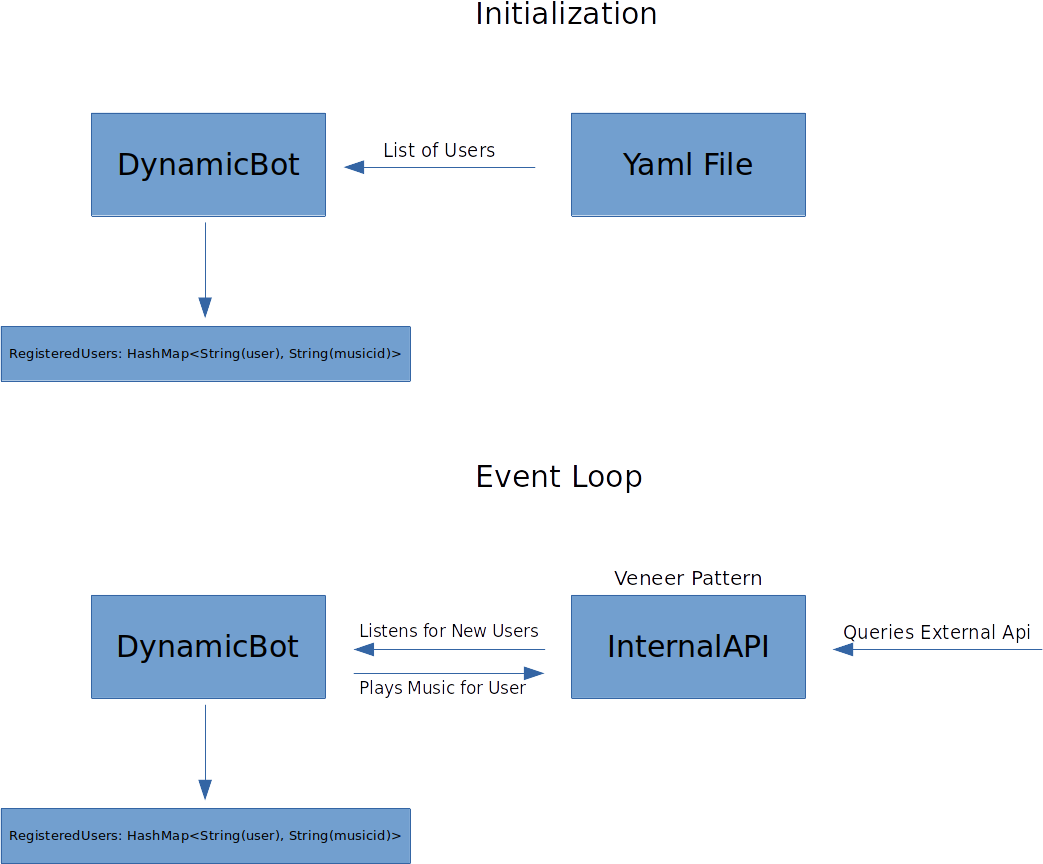

I ended up using yaml to do this. I prefer using yaml when working with data that's meant to be edited by people. I was hesitant at first, since I expect json to be more reliably supported. But the serde json library I've used in rust has yaml bindings as well. If this isn't supported at any point I can always convert the yaml into json; the api is exactly the same.

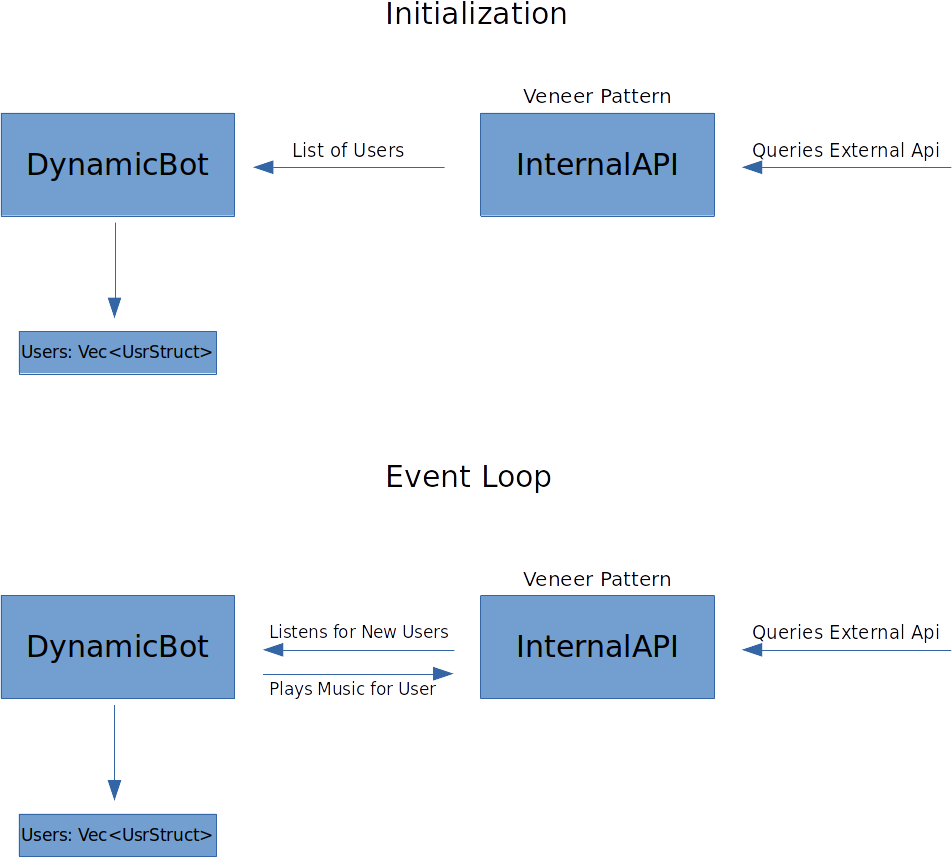

I did make a few changes. I created a registered user field in the DynamicBot to store a HashMap with usernames as keys and music identifiers as values. This gets loaded from the yaml file. Then I will go back to using a list of Strings to keep track of users in a channel, as I originally meant to. There's no need for a struct for Users; once the music file plays I don't need to keep track of it.

I've tagged the gitrepo with the state of the codebase right now, here. I ended up commenting out all the code in main.rs. This is ugly, but I'll remove it eventually and it'll let me use it as a reference while I develop.

6/18/2020 - Diagram Update

I realized today that I don't need to store the list of current users in a vector. I'm not attempting to do any exit actions or changing behavior based on current users. This also means the initialization step doesn't require the internal api; so I'll update it to explictly reference loading the yaml file. So I've updated the diagram to remove this.

6/20/2020 - Designing Internal API

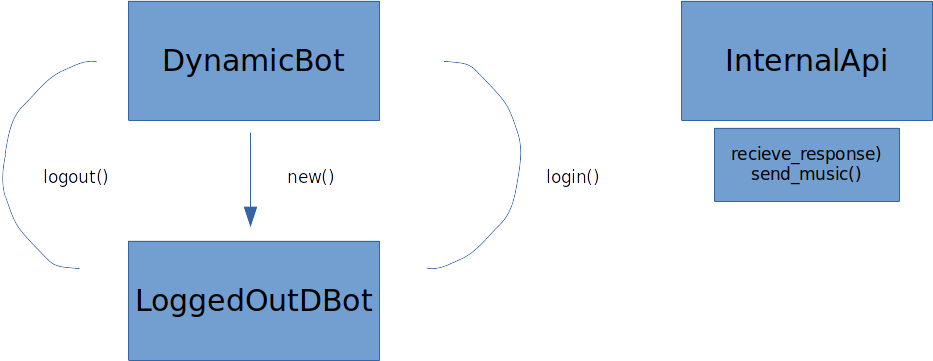

One aspect I need to address with the internal api is how to handle logins. In the previous version I used a struct to implement the traditional state pattern. But, as I noted earlier, the docs have a better idea. I can have the DynamicBot struct return a LoggedOut type that uses a login method to return a DynamicBot. This allows the Rust compiler to keep track of the types and whether methods are valid or not.

For the internal api, I need two methods; one that waits for the name of somebody who enters the channel, and another method that takes the music string.

I've tagged the repo in its current state here.

6/22/2020 - Implementing Internal API

The api I'm using is this one; it seems to be most well supported at the time of this writing. It looked intimidating at first; but the examples were helpful to understand how to approach the implementation.

I want to keep my internal api seperate from serenity; as per the veneer design pattern. So what I did is spawn Serenity in a seperate thread; and use mpsc channels to handle communications between Serenity and my internal api. This is definitely a lot more complex. But the trade off is I can change the external api and keep the rest of my code untouched. I was able to finish the internal api's implementation and next I'll need to make sure the message passers are working from inside Serenity.

6/23/2020 - Channels with Serenity

Sending the channels to Serenity was a little complex. The mpsc channels can be sent to other threads safely, but Serenity shares information across all event handlers, so I can't pass the channels to my explicit target endpoint. This means I need to guard them with mutexes and arcs. The mutexes implement locks and the arcs keep track of the channels if multiple threads were to access them. I won't ever create such a situation, but it is allowed in the code so I have to account for it. This is just Rust forcing me to be very explicity when dealing with concurrency. But they have designed both the Arc and Mutex types to make this as painless as possible.

Serenity also has a way to handle audio playback. This was buried in the (surprisingly good) documentation. But I can easily handle playback using youtube-dl or ffmpeg. Both need to be installed as command line tools, but I had both of them already.

Now I have a working prototype! I was able to log into my test channel and used the youtube-dl endpoint to play music when I joined. There was a small delay to account for the download, but it works!

6/24/2020 - Cleaning Up Code

I cleared out all the warnings; most of this had to do with not handling errors correctly. I also made use of Rust's module system to organize the api a bit better. I added a logout command so I don't always have to Ctrl-C the bot from the command line. I really like the error messages the Rust compiler gives out. They're easy to understand and don't feel like a cryptic mess. Because of this I felt much more confident refactoring my Rust code.

6/26/2020 - Final Thoughts and Objective Analysis

Well, at this point I have the bot in a working state with reasonably clean code structure. Is there more I could do? I could make some quality of life changes so I can join channels with their names and store users with names instead of IDs. If this was a legitimate project, I would probably have to do so. But for this research experiment I don't think it's necessary. The work would really come down to investigating the api until I figured out how the get the information I need.

I'm very pleased with Rust. Most of the annoyance I had with this project was getting the api to work and even that wasn't so bad once I learned how to navigate the documentation. While pedantic, the rust compiler does a great job of telling you why it doesn't like some piece of code you're writing. I also really like the trait system and how Rust handles types. Using object transformation for the state pattern feels very natural. And the trait system allows me to add behavior without thinking about some complicated object structure.

Something I'm less pleased with is how verbose some of the code can be. And it's not always easy to hide code behind functions, because you need to be very careful with references and how you use your variables. This wouldn't stop me from using(or enjoying) Rust, but it's something to note.

So did I accomplish my goals? I'd say so, yes. I refactored the bot into a working version with the serenity api. There are some quality of life annoyances with usage, but it works. I also played around with design patterns and found two natural cases with the state pattern and the veneer pattern. Both patterns provide benefits for their increased complexity. With the state pattern, I learned how to modify a design pattern for use in Rust. And I rejected a use case for a design pattern(command pattern for user info) because it added complexity and wasn't necessary.

However, everything isn't perfect. As I mentioned in this previous project, I want to develop Rust as a secondary language. I did see how that could be difficult in the future. This bot was a just a research experiment, not something I was genuinely enthusiastic about building. This meant my motivation to do so was sometimes weak. I noted how I didn't feel the need to add some quality of life improvements, but if this was a project I was genuinely passionate about; I would've done so without hesitation. I have plenty of these projects but it is hard to justify using Rust instead of Python or C++. The quarantine going on right now means I have time to invest in these Rust maintenance projects, but when everything returns to normal I'm not sure I will be able to so. So my ability to keep Rust as a secondary language will hinge on whether I have personal projects where Rust is genuinely the right choice.

But, this has no bearing on the goals for this project, so I am happy with marking it as successful.